Jelly Fish Lake

Location

Southern Lagoon, on Mecherchar Island.

Distance from Koror

18 miles, 30-40 minutes by speedboat.

Visibility

6’-18’ (2-6m) depending on the tides and weather.

Level of Diving Experience

Snorkeling only! Ongeim’l Tketau is suitable for every person who is a capable and calm swimmer, although people with allergies to jellyfish should consider wearing protective clothing while swimming among these creatures.

Diving Depth Summary: None

Currents: None

General Information

Jellyfish Lake, or Ongeim’l Tketau as it is called in Palauan, is one of approximately 70 marine lakes scattered throughout the limestone “rock islands” of the southern portion of the main Palau archipelago. Like most marine lakes, Ongeim’l Tketau is accessible only by traversing a ridge, which separates the lake from the surrounding lagoon. The trail is short (less than 1/4 of a mile) with a relatively steep but invigorating middle section; rope guides highlight the path and provide added stability on the rocky terrain. The walk provides an enjoyable introduction to the flora and fauna of the Palau jungle. In the cool under-story, quiet visitors can often see skinks and small, harmless, snakes, spot birds in nearby trees, and with luck, catch a glimpse of a monitor lizard. Interpretive signs help make the most of this trip through the jungle. Visitors emerge from the jungle onto a wooden dock (be careful the dock is slippery when wet!) situated in the northwest corner of the lake and gaze across the lake to the southern edge.

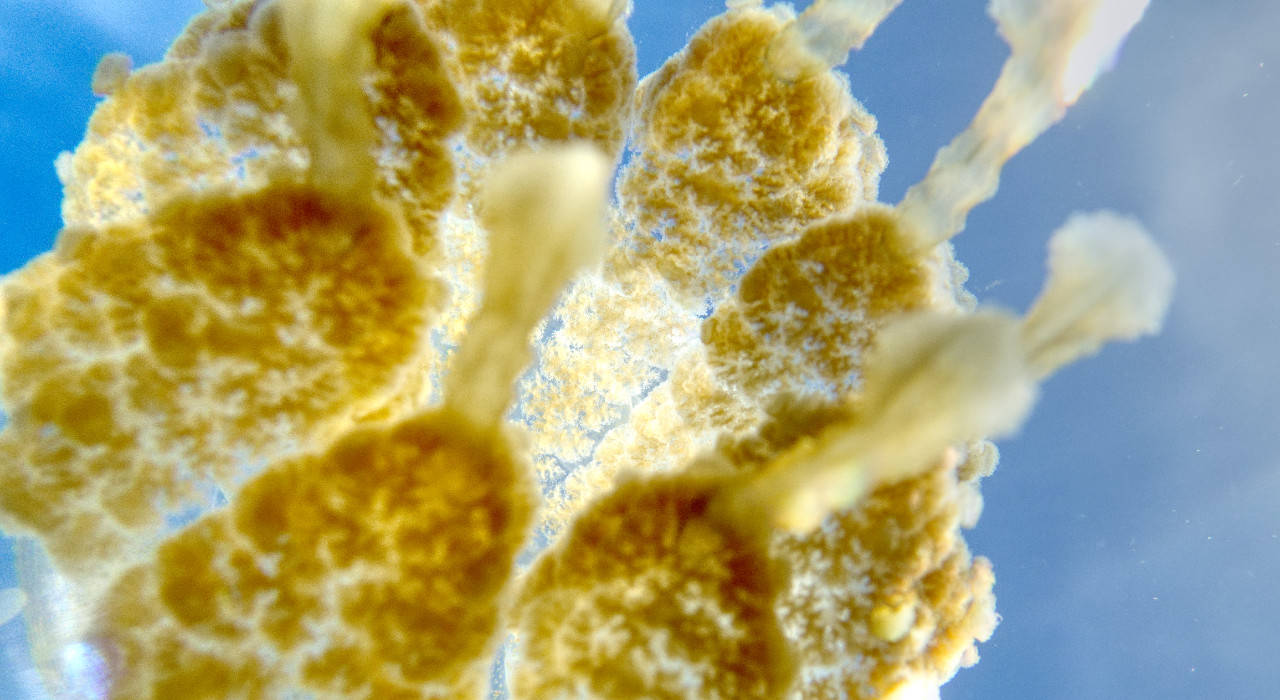

The golden jellyfish (Mastigias sp.), for which the lake is famous, typically can be seen by swimming out of the channel in front of the dock and heading toward the center of the lake. SCUBA is prohibited because the air bubbles exhaled by divers can become trapped in tissue pockets of the jellyfish, air-lifting them to and pinning them against the surface, until the trapped bubbles eventually force their way through the delicate tissue, leaving a nasty wound. Lake formation: Like all of the marine lakes, Ongeim’l Tketau, can be thought of as a young lake in an old rock island. Palau’s remarkable rock islands formed millions of years ago as tectonic forces slowly pushed coral reef out of the ocean, creating land with the topographical characteristics of reefs: a complex network of high ridges and steep faces interspersed with depressions, all formed of limestone now perforated by channels and fissures. The marine lakes are the product of the porous nature of the islands in relation to the height of the surrounding ocean (sea level), which, over the last 25,000 years, has changed profoundly in response to changes in the earth’s climate. During the earth’s most recent glacial period, approximately 20,000 years ago, vast amounts of water formed massive glaciers, and, consequently, sea level was 330 feet (100 m) lower than today. As the climate warmed subsequently, the glaciers gradually melted returning water to the seas. Approximately 10 to 12,000 years ago, sea level reached a sufficient height to flood the channels and fissures of the rock islands, creating marine lakes in depressions within the islands. (Imagine placing a colander in an empty sink and then filling the sink with water.) The marine lakes remain connected to the sea and, on a daily basis, the influence of sea level on the lakes can be witnessed as the tides rise and fall within the lakes in response to tidal changes in the surrounding lagoon.

Reef Formation

The lake reaches 100 feet (30 m) at its deepest point; however, plant and animal life are restricted to the top 45 feet of the lake. Below this depth, the water lacks oxygen and, instead, contains high concentrations of the toxic compound hydrogen sulfide, which precludes all organisms that require oxygen to live, including humans. The hazards presented by this compound are responsible in part for the ban on SCUBA diving in the lake.

Marine life

The marine life of Ongeim’l Tketau differs substantially from that encountered on a typical dive in Palau and thus provides a refreshing experience. The golden jellyfish (Mastigias sp.), for which the lake is famous, are found in great abundance (5 plus million animals) throughout the lake, often accumulating in spectacular aggregations along the edges of shadows cast by the mangrove trees that line the lake’s shore. This tendency to avoid the shady shore, along with a propensity to migrate, are behaviors the jellyfish inherited from their ancestors, the other golden jellyfish, Mastigias Papua, which inhabits the coves of Palau’s lagoon. Over thousands of years, evolution has shaped these ancestral behavioral tendencies to meet the unique demands of living in Ongeim’l Tketau. So now, every sunny day at first light, the jellyfish begin migration in the western basin, where they overnight, to reach the furthest illuminated edges of the eastern basin by mid-morning, after which they reverse their course to return to the western basin by mid-afternoon and complete their one-kilometer long trip. This lake-specific migration keeps the jellies in the sun and away from the dark edges of the lake where the graceful but predatory anemone Entacmea medusivora lives, awaiting those individuals who pass too closely to their extended tentacles. Sunlight is an essential element in the lives of the golden jellyfish, which, like reef-building corals and the ancestral golden jellyfish of the lagoon, derive their color and much of their energy from algae that live in their tissues. Like all photosynthetic organisms, terrestrial or aquatic, the algae use sunlight to produce sugars, which they share with their animal hosts. In turn, the jellyfish provides the algae with a safe haven from predators, a mobile home that keeps them in the sun, and a convenient source of essential nutrients in the form of the metabolic wastes. While the jellyfish are highly dependent upon the sugars provided by the algae, they are not their sole source of energy. Indeed, golden jellyfish supplement their diet by using stinging cells called nematocysts to capture minute animals that live in the open water of the lake. Thus, just like jellyfish everywhere, the golden jellyfish of Ongeim’l Tketau do sting.

This fact belies the most persistent myth about these jellyfish: that they are stingless, a condition said to have evolved uniquely in this lake as the jellyfish gradually grew to depend solely upon their algae for energy. However, as the myth of the stingless jellyfish attests, and as thousands of visitors who have swum among these animals will concur, the sting of the golden jellyfish is undetectable (except on sensitive tissue like lips) and no cause for concern. Ongeim’l Tketau is also home to a large population, one million-plus individuals, of the second species of jellyfish, the moon jellyfish (Aurelia sp.). These exceedingly fragile carnivores spend most daylight hours in the deeper waters of the lake feasting upon the same small animals that supplement the diet of the golden jellyfish. Thus, despite their great abundance, the moon jellies do not figure prominently in the visible character of the open waters of Ongeim’l Tketau. Although most visitors are drawn to the lake by the prospect of swimming among millions of jellyfish, beyond this unique and spectacular experience, the lake has more to offer. The curious visitor will find a colorful montage of sponges, sea squirts, mussels, anemones, and algae living upon the extended roots of the mangrove trees spectacularly illuminated by the beams of sunlight that penetrate the thatch of branches above. Multitudes of small fish called gobies make their home nestled among these organisms and cardinal fish lurk in the open water just beyond. Avian life at the lake is also diverse and animated. Spectacular blue-collared kingfishers sit stately and still upon mangrove branches reaching out over the lake, occasionally breaking their trance to trace trademark chord-like paths between branches along the shore. Pied cormorants sit silent and motionless on mangrove branches along the edge of the lake, periodically taking to the water to hunt small prey while white-tailed tropicbirds and fairy terns monopolize the sky over the lake and jungle loudly socializing and intermittently plunging from the sky after the loosely schooled silverside fish that dart among the jellies. Occasionally a large, solitary fruit bat takes to sky above the jungle moving among roosts in the canopy.

Diving

As mentioned above, SCUBA diving is forbidden in Ongeim’l Tketau both because it damages the jellyfish and because the hydrogen sulfide in the bottom layer of the lake poses a serious risk to human life.

Fascinating Facts (or answers to commonly asked questions about Jellyfish Lake):

Are there other marine lakes with jellyfish populations?

Yes, Ongeim’l Tketau is one of at least eight lakes in Palau that contain large populations of either the golden jellyfish, the moon jellyfish, or both. However, with the exception of Ongeim’l Tketau, all are closed to tourism under the Koror State Rock Islands Conservation Act. Beyond Palau, there is at least one other jellyfish lake containing golden jellyfish in Kakaban, Indonesia.

How do jellyfish reproduce?

The familiar, swimming animal we identify as a jellyfish (properly called a medusa) is actually one of two very different, relatively long-lived life stages that characterize the life cycle of most jellyfish species. The second life stage is the polyp, a minute (only several millimeters in size), a free-living animal that looks somewhat like a very small anemone - complete with a mouth surrounded by a ring of tentacles situated on the end of a stalk that attaches the animal permanently to its habitat. The medusa and polyp life stages are related to each other in the following way: medusae give rise to polyps and polyps produce new medusae. The transition between one life stage and another occurs cyclically in the following manner. Like humans, a given medusa is either female or male. Female medusae produce eggs and male medusae sperm. The fertilization of an egg by a sperm produces a small, round, swimming organism called a larva. Upon maturation, which takes several days, the larva locates a suitable habitat on the side of the lake, usually, a rock, dead leaf, or piece of wood, stops swimming, and settles down on it. The larva then undergoes a radical physical change, transforming itself from a round, motile ball of cells into a non-motile polyp with tentacle-surrounded mouth and supportive stalk. The polyp then lives its entire life attached to that object, using its tentacles to capture and ingest small animals from the environment around it. Polyps are reproductively more flexible than medusae (which can only give rise to polyps via sperm and eggs and a motile larval stage) in that they can produce both new polyps and new medusae. Individual polyps give rise to new polyps by producing a small outgrowth from their body that detaches, swims away, settles on the bottom, and quickly grows into a replicate of its parent, complete with all the reproductive abilities of its parent. Alternatively, under certain conditions, a polyp will produce a new medusa by physically transforming its mouth and tentacle end into a baby medusa, which pops off, swims away, and matures into an adult medusa. The remaining polyp then regrows a mouth and tentacles and lives on with the potential to produce additional medusae and polyps. This somewhat bizarre life cycle can easily account for the millions of medusae that inhabit the lake. Reproductively mature medusae produce millions of larva over the course of their lives-giving rise to millions of polyps. In turn, these polyps can produce untold numbers of new polyps each with the ability to produce new medusae. Indeed, in the absence of any predators or other factors that limit the numbers of either medusae or polyps, such profligate reproduction is virtually guaranteed.

How fast does a golden jellyfish grow?

Best estimates suggest that the bell diameter of a golden jellyfish increases at about 1 cm per week on average. (The bell is the top part of the animal that looks like an umbrella.) At this rate, it takes the average medusa around 2 to 3 months to reach sexual maturity, which corresponds to a bell diameter of about 7 cm.

How long does an individual golden jellyfish live?

Again, it has been difficult to estimate the life span of the average jellyfish reliably but it seems likely that a given individual lives about 6 months to a year before dying.

Why does Ongeim’l Tketau lack oxygen and instead contain hydrogen sulfide below 45 feet? Does anything live there?

Over thousands of years, the bacteria that break down dead organisms (that accumulate at the bottom of the lake) have consumed all the oxygen and released hydrogen sulfide into the water. In most lakes, oxygen is replenished and hydrogen sulfide removed as oxygen-rich surface waters are forced down to the bottom by wind blowing across the surface. However, the high ridges around Ongeim’l Tketau greatly reduce the strength of the wind that blows across the surface of the lake. This, combined with the relatively deep nature of the lake and limited tidal mixing, prevents cleansing surface waters from ever reaching its depths. Now, the only organisms that inhabit the waters below 45 feet are bacteria that can live without oxygen and tolerate high concentrations of hydrogen sulfide.

Why is hydrogen sulfide poisonous to humans?

Hydrogen sulfide is poisonous to humans because it prevents the delivery of oxygen to our tissues, which, ultimately, can kill us. Like oxygen, hydrogen sulfide is a gas that is soluble in water. Unlike oxygen, however, hydrogen sulfide can enter our bloodstream directly across our skin. Once in the blood, hydrogen sulfide binds to our hemoglobin (the molecule that binds oxygen and delivers it to tissues throughout our body), which prevents oxygen from doing the same and leads to death by oxygen deprivation (asphyxiation). Recommended behavior around the jellyfish: Jellyfish are very delicate animals whose bodies are comprised primarily of water (~ 96% of their weight is water) infused throughout a network of tissue. Thus, water provides virtually all of their structural support (it is their bones), allowing them to grow large, and appear robust, without any rigid tissues. The aqueous nature of these animals leaves them exceedingly vulnerable to damage. Please do not remove the animals from the water, as gravity, pulling on the mass of their waterlogged tissues, will stretch and tear them. Try to float serenely on the surface using slow, gentle fin kicks to propel you above the animals. Avoid quick actions with both your hands and feet as you can easily snag an animal in your hands or on your fins unintentionally tearing or slicing them.

Written by Dr. Laura Martin and Mike Dawson